How A/B Testing Became the Default

A/B testing became the default method for digital teams because it’s fast, simple, and gives a clean yes/no answer. Anyone on a marketing or product team can launch a test without needing a statistician, a researcher, or a complex analysis pipeline.

Experimentation platforms like FigPii reinforced this behavior. Their workflows make it effortless to spin up a test: pick a goal, create a variant, and hit launch. That convenience shaped an industry culture in which “experimentation” means “run an A/B test,” even when other methods might yield deeper insights.

Industry surveys show this clearly.

According to statistics, 77% of all experiments are simple A/B tests (two variants), not multivariate or multi-treatment designs. This shows how strongly teams default to the simplest possible approach, regardless of whether it’s the most informative.

Big tech helped normalize this mindset. Microsoft’s Bing team famously ran an experiment in which merging two ad title lines into a single longer headline increased click-through rate enough to generate over $100M in additional annual revenue. Successes like these made A/B testing a cultural norm.

Today, Microsoft runs 20,000+ controlled experiments a year across Bing alone, using tests to validate everything from minor UI tweaks to major ranking updates.

The Core Problems With Over-Reliance on A/B Tests

A/B Tests Answer Narrow, Small Questions

A/B tests are practical for micro-changes, such as headline tweaks, button styles, and minor layout shifts. But that’s also precisely why they limit teams. They are effective only for small, isolated decisions, not for meaningful shifts in product, pricing, or experience.

For example, A/B testing works well for small questions like:

A/B tests are great for small questions like:

- “Does this headline perform better than that one?”

- “Will placing reviews higher on the page increase add-to-cart?”

- “Does a shorter checkout form reduce drop-off on that step?”

- “Does a different product image improve clicks?”

- “Which CTA wording gets more taps?”

These are small questions because they focus on a single element on a single page, and the potential outcome is usually a modest lift (1–2% at best).

The problem is that teams try to use A/B tests to answer big questions, the kind that decide whether the business actually grows:

- “Is our value proposition clear enough for first-time visitors?”

- “Is our navigation structured the way customers think?”

- “Are we pricing and discounting in a way that improves profit, not just conversion?”

- “Does our PDP tell a convincing story about why the product is worth the price?”

- “Should we redesign the checkout flow entirely?”

These questions involve multiple aspects of the experience, including pricing, messaging, navigation, and product mix. You cannot answer them by changing a single UI element.

Most Companies Lack Traffic for Statistical Power

Most ecommerce brands simply don’t have enough traffic to run reliable A/B tests. A/B tests only work when you have statistical power, i.e., enough visitors and conversions to tell whether the difference between Variant A and Variant B is real or just noise.

If the difference you’re testing is small (like a 1% or 2% lift), you need hundreds of thousands of visitors per variant to detect it reliably.

Most ecommerce sites don’t come close. Even brands doing 1-2 million sessions per month often can’t detect a small UI lift without running a test for 6-12 weeks, which slows the team’s ability to learn what works and make confident decisions.

This leads to three standard failure modes:

- False positives: A test looks like a “winner” when the effect is actually random noise.

- False negatives: A test shows “no difference,” even though the change might actually be better, but the site lacked sufficient data to detect it.

- Teams shipping inconclusive results: Because they can’t wait 8–10 weeks, they roll out whatever “looked good,” which creates a cycle of guesswork disguised as data.

They Tell You What Happened, Not Why

You see the result that one version “won,” but you don’t know what actually drove that behavior.

Was the page clearer?

Did users feel more confident?

Were they confused but pushed through anyway?

Did something unrelated happen at the same time?

Without knowing the real reason, teams start making decisions based on guesswork. You miss hidden UX problems, you repeat changes you don’t fully understand, and you end up trusting numbers that don’t tell the full story. That’s how A/B tests create blind spots and a false sense of certainty.

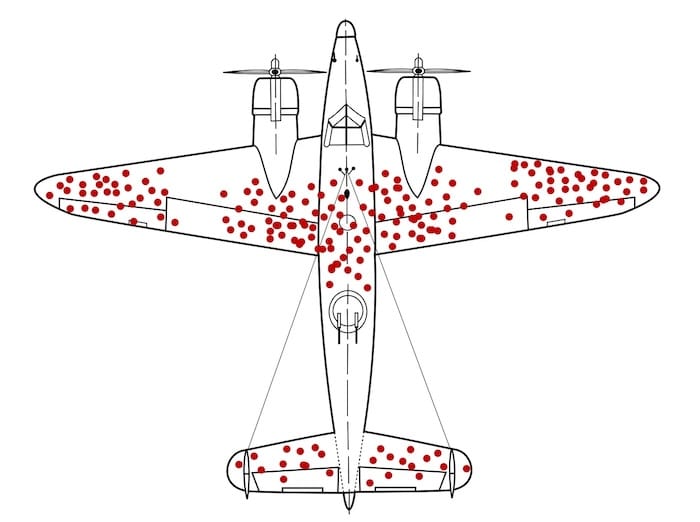

This problem is similar to the classic World War II survivorship-bias story.

When the military examined bullet holes in planes returning from missions, the fuselage appeared riddled with hits while engines seemed untouched. The initial instinct was to reinforce the areas with the most holes until statistician Abraham Wald pointed out the obvious: you only see the planes that survived. The ones hit in the engine never returned. The real insight was hidden in what wasn’t visible.

WWII aircraft with bullet holes mapped on returning planes, showing how A/B tests only show data from users who ‘survived’ the funnel, not those who dropped off. A/B tests work the same way. (Source)

They show you the behavior of people who made it through the funnel, the “survivors.” But the most important information is often in what you can’t see:

- Why people hesitated

- Where they got confused

- What they didn’t understand

- What made them abandon the experience altogether

The test result tells you Variant B won, but it doesn’t tell you whether it won because:

- The value proposition became clearer

- Users felt less anxious

- The layout reduced cognitive load

- The change accidentally nudged people forward

- Or, a completely unrelated variable influenced the outcome

You only see the outcome, not the mechanism.

And just like the WWII aircraft analysis, focusing only on the visible data (the converters) can lead you to reinforce the wrong parts of the experience. Without diagnosing why something worked or failed, you end up optimizing the bullet holes instead of fixing the real vulnerabilities.

Teams Run Tests on Fundamentally Broken Experiences

Many companies run A/B tests on pages that are already flawed (think, slow load times, confusing navigation, weak product information, unclear value propositions). With these issues, even a “winning” test doesn’t fix the real problem. It just finds the least bad version of a bad experience.

You’ve probably seen this in your own funnels:

- The page loads in 4–6 seconds on mobile, but the team is testing button text.

- Users can’t understand the product, but the team is testing hero images.

- The navigation doesn’t match how customers actually shop, but the team is testing CTA color.

- Product pages lack sizing clarity or reviews, but the team is testing layout tweaks.

This is why you only see small wins. The base experience is already weak, so no matter what you test, the improvement will always be tiny. You’re polishing something that actually needs to be rebuilt.

They Optimize Short-Term Uplifts, Not Long-Term Metrics

A/B tests measure immediate actions, such as clicks, add-to-cart, and purchases, within the same session.

But ecommerce businesses care about long-term outcomes:

- Customer lifetime value (LTV)

- Repeat purchases

- Margin and profitability

- Subscription retention

And these long-term outcomes often clash with what looks like a “win” in a short-term A/B test. In other words, something that lifts conversion today can easily hurt your profit, repeat purchases, or customer loyalty later even though the test result looks positive in the moment.

Here’s what this looks like inside most ecommerce teams:

- A large discount often wins an A/B test because it increases immediate conversion. However, the company makes less money on each order, so overall profit declines even though the test “won.”

- A simplified checkout can increase purchases, but it may also make it easier for impulse buyers, fraudulent orders, or accidental purchases to slip through. None of these problems shows up in the A/B test results.

- Urgency or scarcity messages can boost short-term conversions, but they often reduce repeat purchases because customers feel pressured. The test looks successful, but loyalty drops.

- Showing more products on a page can increase clicks, but also overwhelm customers. This is the classic “choice overload” effect, demonstrated in the famous jam experiment by Iyengar and Lepper, where a larger assortment attracted more interest but led to fewer purchases. More options feel exciting in the moment, but they often reduce decision confidence and long-term value.

Jam experiment showing 30% purchases with 6 options vs. 3% with 24 options, showing how a variant that increases engagement can still reduce conversions, just like misleading A/B test ‘wins.’ (Image Source)

What High-Maturity Teams Do Instead

4.1 Use a Broader Experimentation Toolkit

- Sequential tests, holdouts, quasi-experiments, switchbacks, etc.

4.2 Improve Hypothesis Quality Through Research

- Experiments are grounded in user insights, not backlog guesses.

4.3 Test Bigger Levers

- Messaging, templates, IA, bundling, personalisation — not just buttons.

4.4 Tie Experiments to Business Outcomes

- LTV, contribution margin, repeat rate, acquisition efficiency.